Why US Should Partner with Non-Persian Nations in Countering Iran’s Aggression

Up until now (and likely for at least the last 70 years or so), the US foreign policy has consisted of identifying one ally, partner, or counterpart, and dealing with that party onwards until either US policy changes or that party’s does, which would leave the US stabbed in the back.

Such one-sided course of action has proven particularly unwise when dealing with tribal or sectarian societies or failing or failed states. Poor intelligence stemming from focus on only one actor led to surprises, flawed strategies, excessive rigidity, and inability to pivot at a key moment.

Failing to predict turning points in other societies thanks to the tunnel vision of depending on a single source for information had the US foreign policy elites, national security apparatus, and pundits easily hoodwinked and unable to react to major international events, be they the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the emergence of Taliban in Afghanistan, Chalabi’s treachery in Iraq, the Arab Spring, or the rapid downturn in Venezuela. Nothing in recent events shows that the United States has learned from history. In Iran, for instance, the United States largely remains dependent on the “central” Tehran-based opposition, with which it has been working, with various degrees of success for decades.

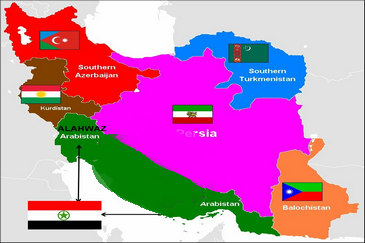

The silence on the fate of non-Persian nations of Iran from both the previous administrations and the current one has been deafening. Although some Iranian individuals and entities have been slapped with sanctions for various human rights violations, the disproportionate nature of arbitrary arrests, tortures, and executions in the peripheral regions where many of the Ahwazi Arabs, Kurds, Turkish Azeris, Baluchis, and others residents has not been noted by US public officials. Together, these nations comprise approximately 50% of the Iranian population (and according to some sources, even more than that), yet remain largely isolated from human rights defense work, sociological studies, or mainstream news coverage. Although their protests against the regime’s discriminatory policies generated protests and uprisings for years prior to the New Year’s Protests recently, none of those events figured into US policy concerning Iran.

Part of the reason has been due to the fact that the powerful Iran lobby groups in the US were largely in control of discourse, and the US policymakers simply had no reliable access to information or voices of dissent coming from the non-Persian nations. But that is only part of the story. Truth be told, there is little evidence that the US intelligence or policy circles had any real interest in hearing perspective that challenged the conventional and convenient narrative that made the story of the “central” opposition so easy to deal with. Exploring peripheral regions would have been difficult and dangerous work.

US-based travelers do not have easy access to some of those areas, and for US intelligence to meet representatives of these groups abroad would mean developing long-term relationships of trust with entire nations, whose narratives clashed with the traditional story of Iran from before the Islamic Revolution. It made outreach work more complicated, not less, because taking into account several different histories, cultures, and visions of the future means that much more coordination efforts and figuring out how any or all of that fits in with US interests in the region. And the conventional wisdom dictated: keep it simple, and the US then will have fewer headaches to deal with. Now, as a result of this misguided perspective, the US has more and bigger headaches on its hands.

Rather than bringing these nations together and countering Iran’s divisive propaganda, the US opted to focus only on the Tehran-based opposition, which has been infested with government informants, paranoid about each other and everyone else, and at times disorganized and subverted by manipulative pro-government elements. Leaders of the mainstream opposition had little interest in the specific national stories of those living in the periphery, and did not seek to address exploitative and colonialist policies imposed first by the Shah, and then exacerbated by the Islamic Republic. With little common ground, the central opposition, in a series of protests that later became known as the Green Movement”, received no support from Azeri Turks, and was soon subverted by the “Reformist” regime elements.

The truth is, if the goal is ultimately a free Iran, a stable and prosperous Middle East, and peaceful coexistence between different nations with diverse cultures and interests, they should all have a seat at the table in the making of their future. By choosing to focus on only one portion of the population in Iran, the United States, first, engages in a discriminatory policy that mirrors the narrow-minded thinking of the Iranian regime itself (and thus does more harm than good), and second, loses out on an important opportunity to gauge the different interests and to build grounds for common dialogue and the overcoming of the differences that create the divisions and stand in the way of a better future for everyone. US is not in the position to “choose” one set of oppositions over others, as though approximately 50% of the country does not exist. This is not the sort of attitude that will be helpful, and it is costing the United States valuable relationships, intelligence, and allies in the region already fraught with sectarian divisions and conflicts.

Furthermore, neither the oppositions nor the Trump administration should view the United States as a “savior” of Iran and the Middle East. The people, whose stake is in their country and in the future of the region are ultimately the solution to the problems that plague Iran and the surrounding countries. US, however, could and should be a friend, a backer, and a partner in the building and creation of a better, peaceful, secure, free, and prosperous future. There are many ways it can lend assistance, while the populations of everyone suffering from Iran’s cruel aegis develops a viable strategy for displacing the regime with a federal system that will accommodate the various interests and cultures.

During the bulk of the protests, for instance, the population clamored for widespread coverage, including, potentially military satellite cover that, which the mainstream media could or would not. That need became particular acute when the regime cracked down on communications, including mobile apps. And to the extent the information got out at all, it did not touch on the peripheral regions. Even regular reporting by the few English-speaking activists from these regions did not reach the wider audiences in the United States. Having a US satellite in the area would have been a provocative but daring step that would have sent a strong message to the regime, and an equally important message of the Trump administration’s readiness to offer practical support, not just words to everyone who was suffering, at least in the form of having their voices heard.

Second, the US government-sponsored Middle East-oriented channel Al Hurra, led effectively by Alberto Fernandez, remains one of the few, if not only channels, currently documenting Turkey’s “Olive Branch” operation in Afrin. Its daring journalists should be given an opportunity to connect with non-Persian activists on the ground to the extent possible. If they cannot meet face to face, they should be connecting through whatever social media/video chat options available. Al Hurra journalists speak the relevant languages and can be an invaluable sources of getting accurate and unique information from those regions, informing the world about what is happening on a daily basis, as well as providing a vital lifeline during crises. Connecting to the outside world will boost morale, and help form important relationships, and perhaps lead to long-distance training and skills that can help individuals improve their personal situations in some small ways.

Third, US government officials should be discussing these non-Persian nations and their oppression, and possibility for a brighter future in their statements and commentary on the daily basis, to connect to new audiences, boost morale among people who are eager to be allies with the West, and to pressure the regime. They should be particularly speaking out about and humanizing individual prisoners of conscience, who have been arrested or tortured as a result of their ethnic backgrounds, community activism, or discriminated against in the judiciary system solely for the reason of being non-Pars. The world should know that each individual life is important, and should be aware that the regime targets non-Persians for the worst treatment, arrests, and brutality because they are underdogs, are unknown, and are easy to abuse.

For far too long the ayatollahs have been getting away with marginalizing significant portion of their population. It’s time for this unfounded ostracism to end. Additionally, US should be using individual sanctions to punish anyone in the regime connected to oppressive and colonialist policy against any portion of the population, as well as any terrorist and oppressive policies against citizens of the countries where Iran is wreaking havoc. Iran’s expansionism should have real life consequences in more than just talk. The US should likewise push for international action for Iran’s discrimination against non-Persians at the UN and other international fora, which have, up until this point, hypocritically refused to call emergency sessions over protests or other critical situations the citizens of Iran have been facing in the regime’s hands.

Domestically, the US should welcome activists representing non-Persian communities to testify in Congress about the conditions of their communities abroad, and their local needs in getting their voices heard from behind the Iran regime propagandists and infiltrated outlets. They should be invited to meet with the State Department officials to offer their policy recommendations on the basis of their knowledge of their own country. They should be integrated with any genuine and trustworthy Iranian oppositions and be accepted by the media. Think tanks, and human rights organization on equal footing with their Fars counterparts.

Work with the US intelligence should be a two-way street. Non-Persian nations can be valuable resources of local knowledge, culture, and actionable intelligence on Iranian bureaucracy, military, and intelligence operation, but the US, as a partners should be offering clandestine assistance through secure channels, which is entirely possible. Iran’s borders are porous and there are no shortage of ways to smuggle items and people in and out, particularly when the regime is struggling with internal weaknesses and external operations. Non-Persian activists should be given preferences for any relevant cultural exchange programs, and an opportunity to visit the United States above anyone else. There is lack of knowledge about these communities in the US, and these groups, which have social motives to oppose the regime, are less likely to be infiltrated by the regime. Furthermore, known and trustworthy activists from the same communities already in the US, can provide invaluable help in vetting them, which is significantly more difficult with the Fars population and their complicated relationships with the high level regime contacts.

Non-Persians should also qualify for humanitarian aid and cultural grants, which would allow them to preserve their indigenous identities and languages, to document their sites, before they are destroyed by the regime or as a result of forced negligence, and to rebuild their lives in spite of regime’s best efforts. Individuals with a stronger sense of identity, who are more secure, can think ahead past a sense of victimhood and in terms of investment into the region. If they are trained to have valuable skills, they can do a lot more independently, and that will cost less to the US and other regional allies in the long run. The US should also allow regional state allies to provide more backing to these nations.

At the end of the day, knowing that there are real and serious consequences of having state actors providing direct and vital help to these peripheral peoples, will put pressure on the regime to move away from blatantly discriminatory actions. Being involved with these regional state allies and working together closely with these nations will create a mutually beneficial relationship of trust. If US knows what is going on, it can be at ease and less worried about losing control over the situation. For that region, I would urge these regional state allies to reach out to the administration in a friendly way and work together to coordinate these actions step by step to avoid unpleasant surprises, misunderstandings, miscommunications, and create an atmosphere of mutual respect, as well as clear and shared goals.

The US is faced with an amazing opportunity to make close allies and good friends who are looking to get closer to the West, to work together in order to shift to a better government system in Iran, to counter Iran’s aggression, and help create a free, peaceful, prosperous and stable Middle East – exactly what is in the interests of the United States. I hope the wiser voices in the administration take this opportunity for a start in a long and productive engagement process and in the building of partnerships that will outlast the regime and bring in a new era that will benefit all involved.

By Irina Tsukerman

Shared: aLiBz